Christina A. Roberto is Mitchell J. Blutt & Margo Krody Blutt Presidential Associate Professor of Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania. Alyssa Moran is Adjunct Assistant Professor of Health Policy & Management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Kelly Brownell is Robert L. Flowers Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Public Policy at Duke University.

The system of food labeling in the United States does not make it easy for consumers trying to assess the nutritional value of the foods they buy. Now, the Food and Drug Administration can do something about it.

More than 40 countries have adopted easy-to-understand, front-of-package nutrition information showing, at a glance, which foods are more — or less — healthful. Thus far, the United States has not required front-of-package labeling, relying instead on the food industry’s voluntary efforts, laden with confusing numbers and percentages. Compare that with the “excess sugar” stop signs you’ll see in Mexico, the Nutri-Score system used in France, or the Health Star Ratings in New Zealand.

Only recently did the idea of a mandated, government-sponsored label gain traction in the United States. Last year, the FDA announced it would undertake consumer research on the topic, with the intent to issue a proposed rule in June. That could mean a shift to the kind of intuitive labeling that signals immediately whether a product contains ingredients you would prefer to avoid.

The only thing standing in the way: the food industry. It favors a label that displays grams or milligrams of key nutrients along with percent Daily Values — much like the Nutrition Facts Label currently on the back or side of packages. The FDA could instead opt for a simple label that uses the words “high in” to indicate when a product has more than recommended amounts of sodium, saturated fat or added sugars. This sensible, science-based label could be strengthened further with the addition of an easily recognizable symbol such as an exclamation point.

By using symbols, colors and simple language, front-of-package labels adopted by other countries have educated people about what’s in their food, helped them make healthier choices and even encouraged companies to reduce salt and sugar in their products. The numeric labels supported by the food industry, by contrast, have consistently been shown to be more difficult to understand.

With enormous profit in highly processed, nutrient-poor foods, it is to be expected that food industry groups — the American Beverage Association and Sugar Association, among others — would favor labels that make it harder for consumers to discern which products are healthier than others. Many of these same food companies have been fighting consumer-friendly front-of-package food labels for nearly two decades. In 2010, the Institute of Medicine(now the National Academy of Medicine) published its first report recommending a nationwide front-of-package nutrition labeling system. Soon after, food companies launched Facts Up Front – a voluntary, industry-sponsored labeling system that now appears on many packaged foods and beverages. This helped industry delay regulation for more than 10 years.

Below are nutrition labeling systems used in countries around the world and three types of labeling systems being considered by the FDA. They illustrate the obvious benefits of a simple labeling system that avoids numbers, percentages, and conflicting information.

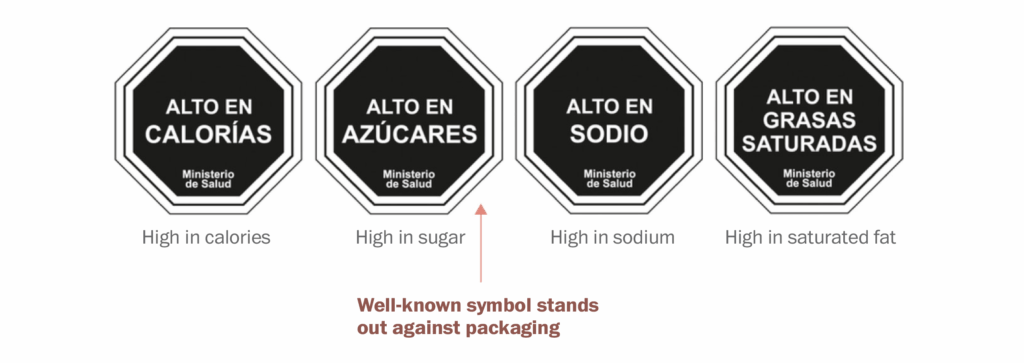

Chile

The warning labels appearing on packaged foods and drinks in Chile serve as a model that many Latin American countries have followed. The labels are consumer-friendly because they use a well-known symbol (the stop sign), their borders and shapes stand out against the packaging, and they highlight the key nutrition information consumers need. Since their implementation in 2016, food companies have reduced sugar and salt in their products to avoid carrying a label and Chilean families have purchased fewer sugary drinks and less sugar in response. Products carrying a warning label cannot be marketed to children or sold in schools.

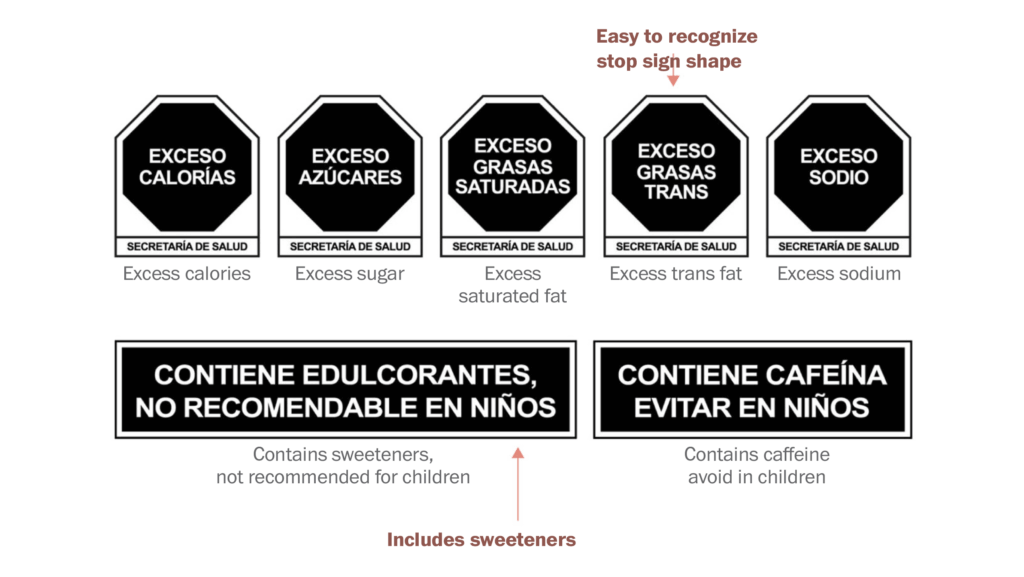

Mexico

Mexico adopted stop-sign-shaped warning labels in 2020. Its labels also include mandatory disclosures of non-sugar sweeteners, such as sucralose and stevia. This was done because, in Chile, after the front-of-package labels were introduced, food manufacturers increased the use of non-sugar sweeteners, particularly in products that reduced sugar to avoid carrying a label. This type of disclosure is something the United States should consider as well.

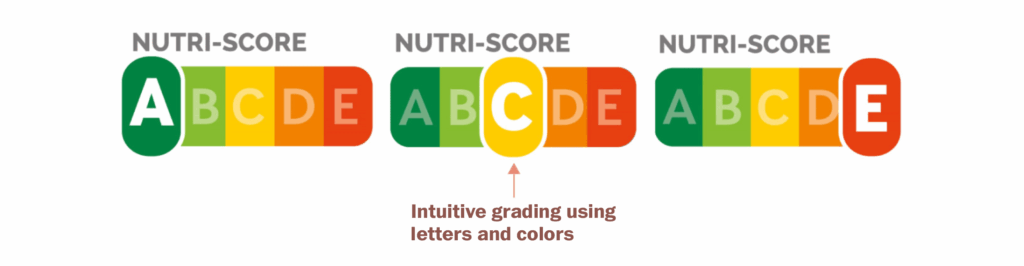

France

The French government adopted the voluntary Nutri-Score labeling system in 2017, and many countries in the European Union have since followed suit. Nutri-Score works well because it assigns a score to a product based on its nutritional profile and uses a letter grading system with colors (green means go; red means stop) for consumers to quickly understand the nutrition information.

New Zealand

This Health Star Ratings system has been voluntarily adopted in Australia and New Zealand. The label makes it easy for consumers to choose healthful products by assigning a score that is represented by stars; healthier products earn more stars. The Health Star system has encouraged companies to reduce sugar and salt in their products to attain higher ratings.

United States

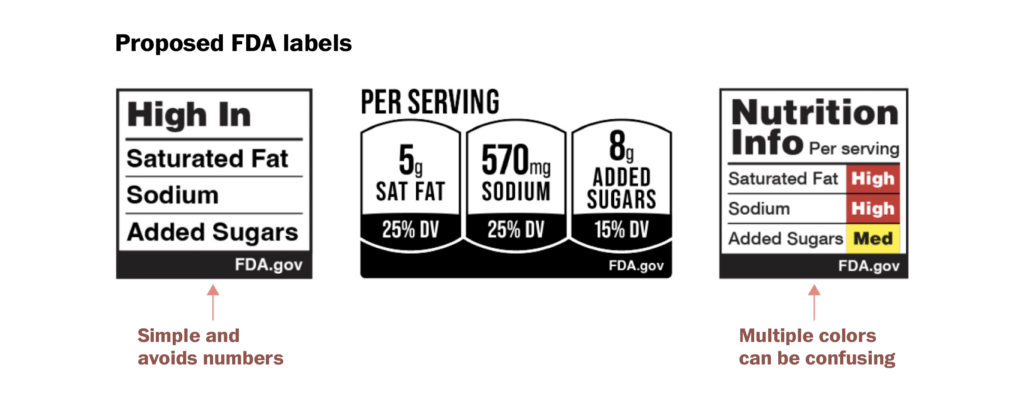

First Amendment issues make it difficult for the United States to adopt labels used in other countries, but the FDA has identified some great options. The “high in” label on the left has been proposed by the FDA and is superior to the food-industry-backed “per serving” label because it is much simpler: It avoids numbers and percentages and helps the consumer focus on key information. Adding an exclamation point would make it even easier for consumers to notice when making split-second purchasing decisions.

As for colors, the agency has suggested using them, but in a confusing way. The image on the right shows an example. Unlike Nutri-Score, which assigns one summary color to a product based on its nutritional quality, this label assigns colors to individual nutrients. This is like pulling up to a traffic light that is red, yellow and green all at the same time — how would a driver know what to do?

It is crucial that the FDA make a science-based decision, as other countries have done. Most Americans have trouble meeting the recommendations for a healthy diet. Adopting a “high in” label with a symbol puts us on the best path toward increasing transparency in the food supply.